“It took 18 miles of new trail to get around that 800 feet,” Paul Koski explained to me, shaking his head incredulously. “18 miles for 800 feet! I couldn’t believe it. It took years to make that happen, but I really think it was actually a huge improvement for the Paradox Trail.”

I stood leaning against a table saw in Koski’s woodworking shop in a massive quonset hut in the tiny town of Nucla, Colorado. He was sharing stories spanning several decades of history related to the Grand Loop and the Paradox Trail. Folks like Koski rarely receive the recognition they deserve for years upon years of dedication to mountain bike advocacy. The afternoon before, I had finished riding for 53 hours straight to set a new record on the Grand Loop, and although my mind was still a bit foggy from the effort, I was excited to finally have the chance to meet Koski. Whether he realized it or not, his efforts and those of others like him in the area had literally changed the trajectory of my own life years before.

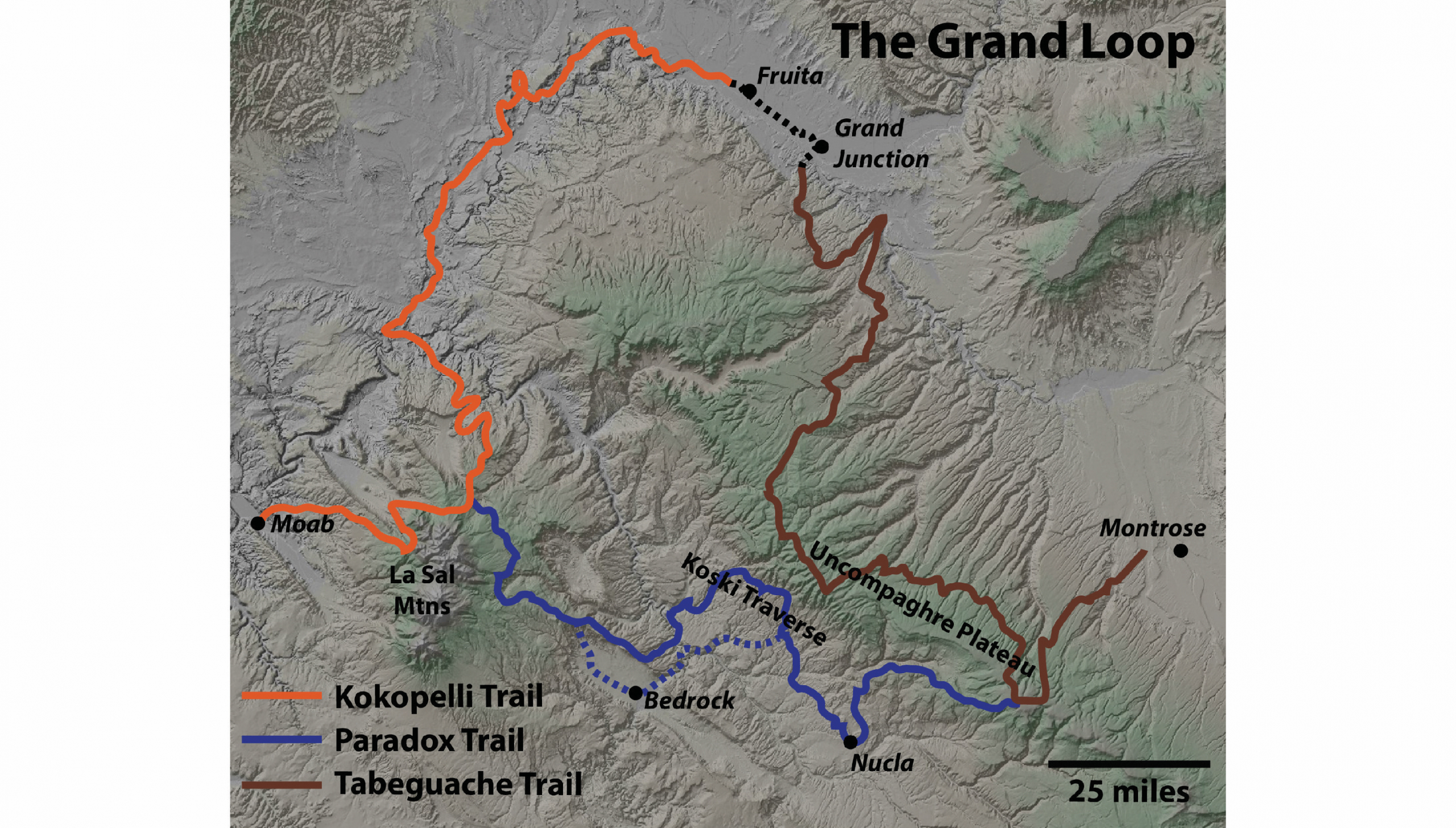

Linking some of the oldest long-distance mountain bike trails in the country, the Grand Loop may be a bit of an unknown and even forgotten character in the evolution of bikepacking and ultra racing in the United States. The 360-mile-long route is wild. It’s remote. The riding is legitimately tough. It’s almost entirely dirt, but there’s very little singletrack or gravel along the way. In the first two installments of this four-part series, I’m excited to share the colorful history of these trails – this article highlights the incredible vision that resulted in the Colorado Plateau Mountain Bike Association creating the 3 long trails that comprise the Grand Loop back in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The second piece will bring readers back to the long-defunct Grand Loop Race and the influence those early participants collectively had on the early evolution of bikepacking races. The Grand Loop has also played a hugely impactful role in my own life – the Grand Loop Race in 2008 marked my entry into both the ultra racing world and bikepacking. In the final two installments of this series, I’ll share more about that ride in 2008 and my return in mid-2020 for a profoundly meaningful ride that also set a new record on the route.

But just where is this route, and how did it come to be? The Grand Loop’s 360 miles of rough riding straddles the stunningly unforgiving country of the Utah-Colorado border east of Moab, south of Grand Junction, and north of Telluride. Making an enormous loop around and over the massive Uncompahgre Plateau and the La Sal Mountains, the route traverses lowlands and canyons along the Colorado River that bake in the summer heat. And the high coniferous forests and meadows hold snow until late spring. The ideal riding season is short, nestled in the weeks between late spring snowmelt up high and furnace-like summer temperatures down low. The landscape and remoteness along the way are as striking as they are daunting. And with more than 40,000 feet of climbing on seemingly endless miles of 4×4 tracks and abandoned uranium mining roads, nothing about the Grand Loop comes easily.

Despite all that, nearly two decades ago, the Grand Loop gained a cult following among the small but growing bikepacking community. Mention the Grand Loop to anyone in that group and it will elicit a grin and distant memories of struggle and unexpectedly outsized reward. But to most other riders who may have heard of it, the Grand Loop exists in something of an enigmatic historic space. Although the Grand Loop will never be popular (for reasons explored later), it’s still out there today, and the riding experience is as phenomenal now as was in 2000 for those who relish the unpolished.

The Grand Loop is composed of the connecting sections of three long-distance mountain bike trails – the renowned Kokopelli Trail and the far less known Paradox and Tabeguache Trails. The creation of these routes in the late 1980s and early 1990s happened in the earliest days of the Colorado Plateau Mountain Bike Association (COPMOBA), an organization well ahead of its time. Well before the popularity of purpose-built mountain bike trails was sweeping across the nation, COPMOBA formed with the admittedly ambitious goal of creating a trail linking Grand Canyon to Aspen, Colorado.

“Before 1988, the idea of long-distance trails for mountain biking hadn’t been considered,” explained Bill Harris, one of the original COPMOBA Board Members. “Of course, the Pacific Crest Trail and Appalachian Trail were in place, but no one had really applied that concept to mountain biking.”

Quickly realizing the challenge associated with creating such a monumental trail across the Colorado Plateau, the founders of the fledgling organization set their sights on a more attainable goal – creating the Kokopelli Trail. Linking Moab, Utah to Fruita, Colorado, the 140-mile trail would traverse the flank of the La Sal Mountains and dozens of miles of rugged desert canyon country. The trail was named for the fertility deity depicted on pottery, petroglyphs, and pictographs found across the Four Corners region from more than 1,000 years. “Kokopelli” is the Hopi name for this deity; to different tribes, Kokopelli is a musician, a trader, a storyteller, a bringer of rain, and more.

The Kokopelli project began in 1988, and land managers from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service were supportive of the trail concept. The route would connect existing singletrack, 4×4 tracks, and gravel roads. Short sections of new trail required to bridge gaps between existing routes were quickly approved as environmental review and approval processes for trail construction by public lands managers were in their infancy. It didn’t take long to finish the project and pound countless Carsonite posts into the ground to mark the new route – by 1989, it was complete!

The following year, Harris and COPMOBA set their sights on another 140-mile-long route connecting the Colorado towns of Montrose and Grand Junction – the Tabeguache Trail. The trail would climb out of the broad, dry Uncompahgre Valley to the crest of the Uncompahgre Plateau at 10,000 feet among aspens and fir trees before meandering along the crest and rugged east slope of the plateau. Toward its northern terminus, the trail would drop into Junction near Colorado National Monument.

The Tabeguache Trail is named for the group of Northern Ute who traditionally spent part of the year in the area, the Tabeguache, or “People of Sun Mountain” (the peak known to the Tabeguache as Sun Mountain was later named Pike’s Peak by settler-colonists). The Tabeguache and other Ute (Nuu-ciu) bands in the area were forcibly removed from Colorado and sent to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in northern Utah.

The Tabeguache Trail was completed in 1990 and required nine miles of new trail construction. Additional sections of singletrack along the route have subsequently been built. At that same time, COPMOBA and the BLM both began to shift their focus to shorter mountain bike trail networks closer to communities.

In 1994, Harris organized a supported ride on the Tabeguache and Kokopelli Trails with the goal of also investigating a potential link between the two – the future 100-mile-long Paradox Trail. Joined by a few friends, including Koski, and Fred Mahaney from Bicycling Magazine, the vision for the Paradox came together. Koski lived in the tiny town of Nucla at the base of the west side of the Uncompahgre Plateau. Nucla was a uranium mining boom town, but that boom had come to a close amid the Cold War, leaving behind thousands of jobless miners and a contaminated landscape. Koski had spent years riding the extensive network of old mine tracks that cling to sandstone canyon walls and climb steeply up the side of the plateau above. He helped the group navigate from the San Miguel River up to the crest of the Uncompahgre and the Tabeguache Trail. The route included a seldom-traveled trail across the strangely lush Glencoe Bench, a trail Mahaney called “Bear Alley.”

The Paradox Trail concept had been pitched a couple years earlier, and the local West End community advisory board supported it. The trail was named for the Paradox Valley, a geologic peculiarity in which the Dolores River flows out of one canyon, across the narrow valley, and into another canyon; most rivers prefer to flow down valleys. Economic diversification was needed as the mines had all closed, and outdoor recreation was one possible avenue to pursue. The BLM and Forest Service were again supportive of the project, and by 1995, the route was approved and then dedicated at a ceremony at the small Bedrock Store in the Paradox Valley. A few years later, Koski led an effort to move the trail off the dirt roads of the Paradox Valley and into more remote and scenic country via a traverse across the lower slopes of the Uncompahgre Plateau. That new section, called the “Koski Traverse,” is demanding and challenging to follow, fitting with the broader character of the Paradox Trail. Along with that effort, the BLM contributed enough Carsonite posts to sign every intersection and at one-mile intervals along the trail.

Over the past decade, new singletrack has been built in the Nucla area and incorporated into the Paradox Trail, and a lengthy reroute was required to get around 800 feet of private land.

“I like to call it 18 miles for 800 feet,” explained Koski. “The landowner decided he didn’t want to have riders out there anymore, and the Forest Service wouldn’t allow a short section of fenceline trail there – it’s the edge of the Tabeguache Special Management Area, and bikes aren’t allowed. So we had to create an 18-mile-long reroute to get around. It was a hell of a process, but I think it actually created a much better rider experience. And it brings the trail to within a half mile of Nucla, so people can easily stop in town to resupply.”

It didn’t take long for the Kokopelli Trail to become one of the iconic trails of the West, and it remains incredibly popular among guided groups, bikepackers, and day riders alike. The Tabeguache Trail sees substantial use on either end, but the middle section remains rarely ridden. The Paradox Trail remains the least traveled of the three. It’s wild, tough, and relentless – classic Colorado Plateau backcountry riding at its best, or worst, depending on what kind of trails one prefers; it’s my personal favorite of the three trails.

And for the most part, Koski doesn’t want that character to change. “I would hope the Paradox doesn’t get ‘dumbed down’ too much. That being said, cycling in the West End will always be a tough ride due to the terrain. I’m also really excited about our efforts for up to 98 miles of new singletrack trails in the Sawtooth area just outside Nucla and Naturita. It could be just ten years to a world class trail experience here.” There are also additions to the trail network on the edge of Nucla in the works over the next couple years.

But back in the late 1990s, a skater-turned-mountain-biker from Grand Junction named Gary Dye set his sights on riding the Grand Loop without vehicle support, and on a second attempt at doing so, became the first to do so with a friend named Omiah Travis. And just a couple years later, the first edition of what became the Grand Loop Race took place. It was arguably the first modern bikepacking race outside of Alaska, and the race went on to inspire the creation of the Colorado Trail Race and the Arizona Trail 300, as well as a group of bikepackers who fell in love with the rugged challenge and remoteness of the Paradox, Tabeguache, and Kokopelli Trails.

To support the organizations that created and maintain the trails that comprise the Grand Loop visit websites of the Colorado Plateau Mountain Bike Alliance and the West End Trails Alliance. Kurt Refsnider will be creating a short guide to riding the Grand Loop itself in the coming months, and some limited information for each of the three trails comprising the loop is available from various online resources (Paradox, Tabeguache, and Kokopelli).